Household moisture primarily resides in the building materials and furnishings in a house. Think your big, damp mattress, for instance.

Damp materials in your house keep your relative humidity high. And releasing humidity into the air means that moisture will eventually find its way inside your couch, or in other furnishings or building materials.

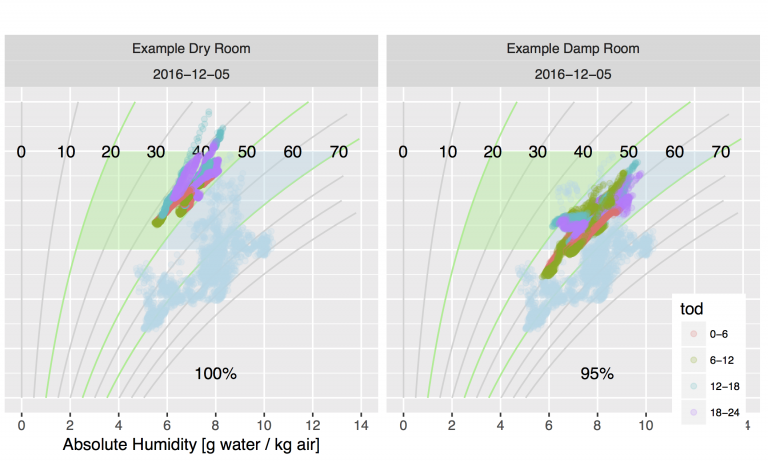

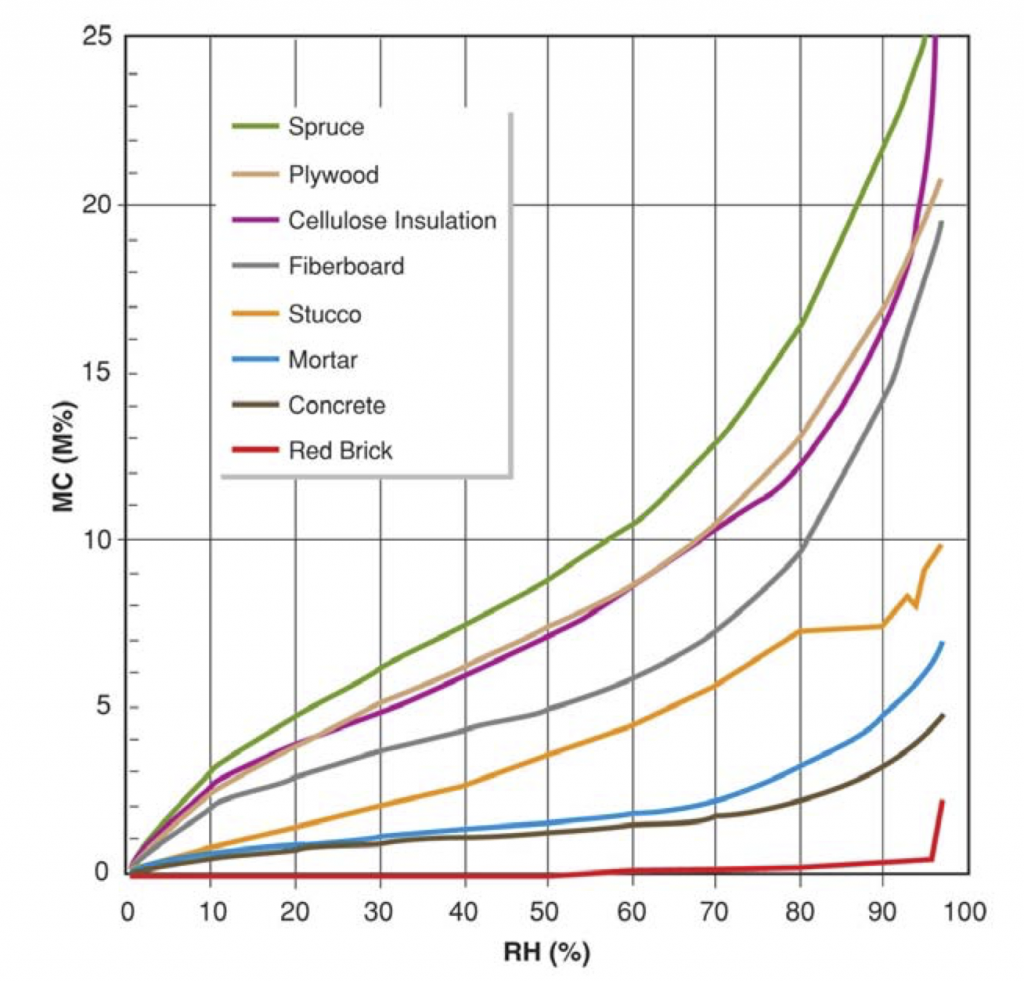

Here is a simple chart of the equilibrium relationship between moisture in the air (RH), and moisture in materials (MC), expressed as a percentage of the mass of the material.

This chart can be read as follows: If you house averages 70% humidity, you can follow the 70% RH line and see that spruce wood (similar to pine), will have about 13% moisture content. Given that your house will have thousands of kg of pine in it, this chart means there will be hundreds of kg of water in that material. And the same with wallboard, insulation, soft furnishings, and your carpet.

For experimental purposes, or for learning with school kids, a simple hygrothermal (heat and moisture) model of a house can be built as so:

Read about our recent research with the Valley Community Workspace community group: ValleyWorkspace.org-BuildingMoistureStorage (PDF)

Also see “The Wetting and Drying of Timber Framed Walls“